GEOLOGY

How California Geology Impacts Palisades Park

MARINE TERRACES AND THEIR BLUFFS

One of the most unique features of California's geology is the marine terraces that line its western coast. The most extensive terraces occur right here in Southern California, with Palos Verdes and Santa Monica rivaling in sheer magnificence.

Southern California terraces are among the oldest and highest. They are one to two million years old, part of the same uplifting process that formed the Coast Ranges. Even to this day they are slowly, incrementally rising. There are even younger terraces out under the ocean thrusting upward.

Such upward lifting of a land mass normally occurs along fault zones. There are three noted fault zones near Palisades Park.

See Faults below.

You can see back thousands of years just looking into her face

TELL TALE SIGNS IN A PROFILE

Terrace soils are generally thin, commonly composed of rock debris, marine fossil fragments, and shells which were all deposited when the terrace was still submerged beneath the sea.

As marine terraces rise from below the sea they face a new tide of terrestrial deposits, thick alluvial deposits of sand and gravel from streams and rivers.

Information from the California Coastal Resource Guide, 1987, California Coastal Commission

LAYERS: A MILLION YEARS IN ONE LOOK

You can see signs of alternating layers, each representing centuries, in the face of the bluff. The layers show the interplay of marine

deposits (rock debris, marine fossil fragments, and shells) and terrestrial deposits

(thick alluvial deposits of sand and gravel from streams and rivers) in the formation of the bluffs.

Information from the California Coastal Resource Guide, 1987, California Coastal Commission

Coastal bluffs are exceedingly prone to erosion

THIS LAND IS NOT STABLE AND WINTER IS A TRYING TIME

"Because bluffs are composed mainly of sedimentary rocks such as sandstones and shales they are particularly prone to erosion.

Grains of quartz, feldspur, and mica compressed into layers of sandstone crumble easily.

When wet, shales and sandstone disintegrate, and clays and muds soften and liquefy."

California Coastal Resource Guide, 1987, p 18, California Coastal Commission

Slumps, sinks, and slips plague the Palisades bluffs

Historic photo of PCH shut down by a massive Park landslide in the 40s.

Santa Monica Image Archive

As recent as March 2013 landslides have had a dramatic impact on the Palisades bluffs—and PCH.

See LA Times Report

Faced with devastating slides the footpath in Palisades Park has retreated over the years.

Yet the agave persists in its role protecting the bluffs!

A trench recently opens in front of the Park's Pergola.

"Areas well known for landslides are Devil's Slide in San Mateo County and Pacific Palisades in Los Angeles County."

—Coastal Commission

For a chronological history of landslides in our area see our History of Landslides page.

Caught between a rock and a hard place

Landslides occur regularly on our California coast and have so for millions of years. Native Americans no doubt witnessed many. It was probably of little concern to them or to the early pioneers. Everyone would simply resettle further inland.

But today there is no place for Palisades Park to go.

The Park's greenspace, its unique biome, is stuck between a wall of development along Ocean Avenue and the edge of the world. Every year soil the park loses to the sea can no longer be regained. In the next century, if the park continues to erode and diminish as it has, even in drought years, the views from Palisades Park could easily be the exclusive possession of the residents along Ocean Ave. But that raises a question: how far down the road do we see? Are we looking ahead to century? Are we managing Palisades Park for the next century?

In the decades ahead what will we need to do to save the bluffs?

Due to the sheer drops and erratic slopes these defenses may not work to save the bluffs

Yet in the examples above we recognize the critical role vegetation plays

—and vegetation is exactly what Palisades Park has used for a century to protect the bluffs

The agave plant at right demonstrates the powerful role Park trees and vegetation play in stabilizing the bluffs. The roots of the agave penetrate deep into the earth binding the soil elements together contributing to the overall integrity of the bluffs.

Every square inch of the park works towards stabilizing the bluffs. The economic, geological, and environmental value of the park would, if put in terms of market value, far exceed the value of any human development bordering it.

The power of one: every tree is critical to protecting the bluffs

Heroic Effort

This heroic tree clings precariously to an eroding park bluff, all the while strenuously fulfilling its role in preserving the bluffs.

Notice the extensive lateral root development. That's an achiever.

When water runs off the park's compacted soils or down artificial park drains, it will not be able to percolate into the soil to sustain this tree's roots.

And the bluffs lose another heroic fighter for its sustainability.

Ground cover acts as a protective sponge and transfer station

At right a thin fragile blanket of grasses creep over the side of the bluffs, protecting the loose top soil from erosion.

Living roots penetrate into the soil, absorbing rainwater, and depositing a layer of organic humus.

This layer of grasses acts as a sponge, a shield of protection, softening the blows of weathering.

It is also an important transfer medium for nutrients and rain water. The darker top soil could reflect the decomposition, an organic process that releases nutrients.

For decades the builders of Palisades Park cultivated such slow sustaining protection to the park's soil.

Learn more: How Grasses Grow

We fear unsustainable human activity is degrading such Park grasses inhibiting the protection they have provided for decades.

A study in contrasts: man or nature

PIPES VS VEGETATION

In Palisades Park there is a system of drains and pipes to divert water runoff especially during heavy rainfall. Heavily saturated soils weigh more and create pressure toward movement. Artificial drains are thus designed to divert rainwater away from slide areas.

Over reliance on artificial drainage, however, has created numerous problems. Drains can burst and wash out whole sections of the park.

According to USC Professor Samuel Goldberg, "Actions that funnel and increase water movement activate landslide triggers. For instance, water lines that break or leak and runoff channels that force water into specific locations pose glaring dangers."*

In the photo of a Palisades Park bluff we might conjecture:

(1) the drainage pipes were in part responsible for the erosion around them.

(2) the natural vegetation at left of the drain pipes is doing a better job in protecting the bluffs.

*Samuel Goldberg "Falling into the Pacific: California Landslides and Landuse."

Eucalyptus Trees, The Park's Secret Weapon

You may have noticed that eucalyptus is one of the main tree species in Palisades Park.

During the time the Park was being developed, from 1907 to 1913, was also one of the two most frenzied periods of planting this Australian transplant in California.

"At the time planters believed variously that eucalyptus would provide fuel, improve the weather, boost farm productivity, defeat malaria, preserve watersheds, and thwart a looming timber famine. First and foremost, however, Californians planted the trees to domesticate and beautify the landscape, to make it more green."*

Decades later we learn these trees not only make the land more green and beautiful; they also serve a vital mechanism by penetrating their roots deep into the bluffs and aggressively absorbing rainwater. This preserves and protects the bluffs. Often orchard owners will complain that the tree is a water hog or an invasive water sucker.

At Palisades Park this unique thirst is a benefit. Rainwater percolates into the soil which encourages root development as the thirsty eucalyptus pursues its love of water. The extensive root development, penetrating rocky porous soils, binds particles together maintaining a stronger bluff that can withstand erosion.

*From "Gone Native: California’s Love-hate Relationship with Eucalyptus Trees" by

Santa Monica and Palisades Park Lie Along Earthquake Fault Zones

A Network of Faults and Earthquakes Intersect

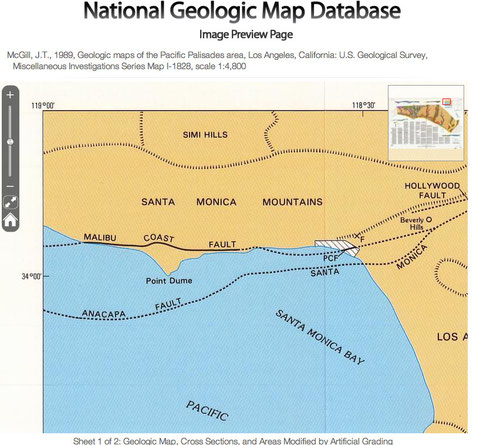

There are two main faults that lie close to Santa Monica and Palisades Park.

According to a Parmelee Geology Inc. report on "Active and Potentially Active Faults in Southern California" there three faults close to Palisades Park.

The Malibu Coast Fault

The Malibu Coast Fault consists of several onshore and offshore en-echelon fault segments trending east-west along the southern margin of the western Santa Monica Mountains....The fault is considered to be “potentially active” as defined in the Alquist-Priolo Special Studies Zones Act of 1972.

The Santa Monica - Anacapa Fault

The onshore extension of the Malibu Coast Fault has been designated as the Santa Monica - Anacapa Fault. While the researchers consider the Santa Monica Fault to be active, the fault has not yet

been zoned active by the State of California.

The Potrero Canyon Fault

"Where the Santa Monica Fault joins with the Malibu Fault, this zone has been referred to as the Potrero Canyon Fault.

The fault has been studied extensively by John T. McGill and described in the publication, “Geologic Maps of the Pacific Palisades Area, Los Angeles, California, 1989".

The fault is exposed in the mouth of Potrero Canyon, extending onshore with a trend of about N75E.

FOR FURTHER READING:

Geologic maps of the Pacific Palisades area, Los Angeles, ... U.S. Geological Survey, Miscellaneous Investigations Series Map I-1828, scale

USGS_I-1828_2 - USGS National Geologic Map Database

USGS_I-1828_1 - USGS National Geologic Map Database